Guest Reviewer: Ravikant Kisana

Multiplexes recently entertained us with Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds — a visually stunning and terrifically tongue-in-cheek take on the World War II genre of movies. However, the movie does beg the question of whether this line of films needed a bold revision. Even as the ‘fanatic’ Basterds hunted down ‘humane’ Nazi soldiers and a comical Hitler, a small section of the audience veritably squirmed in their seats. There was something wrong here. History may be long forgotten, but some sore topics should not be subject to a revisionist pop-culture treatment.

It was with this somewhat disturbing, nagging feeling in my mind that I revisited one of the classics from a forgotten time, directed by Charlie Chaplin. And the genius of one of the greatest film-makers of the 20th century reassured me that once upon a time, film-making was not just about breaking conventions. It was about making a statement, galvanising the masses, providing hope and inspiration when there were none — and doing it all with a comical swagger that simply had to make you smile.

The Great Dictator (1940) by Charles Chaplin, stands as one of the greatest WW-II films ever made; and such is the irony that a film as meaningful and deep in such times should be a classic comedy.

On a lazy Sunday afternoon, reclining snugly with a big bowl of butter pop-corn, you don’t really want to get into that German epic shot in documentary style on Spanish conquistadors from the 16th century. At such times, Charlie Chaplin is your man!

The Great Dictator is his first ‘talkie’ in the true sense of the word. It stars Chaplin in a double-role as a Jewish barber — a lovable and sensitive simpleton — juxtaposed against the comically fiery Adenoid Hynkel, supreme dictator of the fictional land of Tomania.

The film opens with an elaborate World War I sequence where Chaplin, as the Jewish private, valiantly rescues an exhausted commander by the name of Schultz. Hilarious scenes ensue as they pilot a plane to safety, only to crash it later. And in this accident, the ‘Jewish’ private suffers a memory loss.

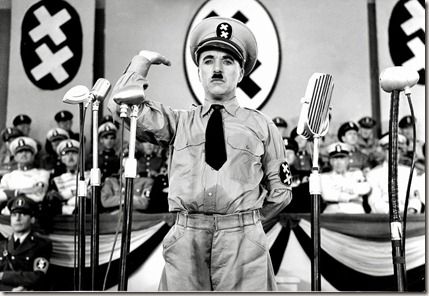

Cut to 20 years later, and Hynkel has taken over as the supreme commander of Tomania. He opens with a fiery speech in an incomprehensible language. Having studied tapes of Hitler himself to mimic his mannerisms, Chaplin goes on to lampoon the ‘Great Dictator’ in his own inimitable style, even as an abbreviated English translation voiceover adds to the humour.

The plot moves into gear when the Jewish private — who was in a mental institution for the last 20 years — escapes to come back to the ghetto and run his barber-shop. Suffering from memory loss, he has no idea about Hynkel’s campaign against Jews and a series of funny incidents take place between him and Hynkel’s storm-troopers. After the war, Chaplin later regretted having made fun of the storm-troopers in the Jewish ghetto, saying had he known the full extent of horrors, he would never have been able to do that. But while making the film, the year was still 1940 and the world had yet to learn of the holocaust; and in so, Chaplin can be forgiven for running riot in the ghetto, if only for making you laugh so hard that your sides ache.

The lust for power, shown by childishly playing with a globe

Hynkel, meanwhile, dances ballet with an inflatable globe, day-dreaming about becoming the emperor of the whole world. It stands as one of the most iconic sequences of cinema, a beautiful interlude showcasing the lust of power in a very childishly innocent manner through a dictator who bounces a globe on his buttocks!

The movie is chock-a-block full of high quality humour as Hynkel discusses plans to invade Osterlich (Austria) with his ‘ally’ Napolini (based on Mussolini), the dictator of Bacteria. Eventually, Osterlich gets invaded by Hynkel and is soon run over by his military might. However, in the crowning moment of glory — Hynkel’s victory rally — the inevitable switch happens. Hynkel is mistakenly apprehended as the runaway Jewish barber, while the actual barber is erroneously assumed to be the great dictator himself.

Thus, the petty barber finds himself addressing a massive victory rally. The world is looking to him. And here Chaplin delivers possibly the most stirring monologue in the history of cinema. The camera zooms in to his face and Chaplin talks directly into it — breaking character, breaking all the rules and breaking the illusionary ‘fourth wall’ of the screen: Chaplin talks to you, the viewer.

He talks to you, to the people, to the world; and in an impassioned speech for the rights of man and what it means to be a human-being, he leaves with the hope for a better world beyond the dark clouds that seem to be gathering. And you can see in the eyes of the man that he truly, fervently believes that these lines spoken into the void of a black camera could go on to change the world. It’s hard not to stand up and applaud.

And so as the movie ends and so does your pop-corn, you end up wishing that the world had really changed. After all, the idea of a bunch of fanatics gunning down the Fuhrer was really not the change you had hoped for…

Rating: 8/10

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When not doling out advice for brands at O&M, Ravikant Kisana can be found decimating two gigantic burgers at a time

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------